Designing ways to identify Child Financial Harms in games

By Sarah Drummond, Director of the School of Good Services

Safety by design is something I’ve written about for a long time. Back in the late 2010s, we began to see a rise of research documenting people experiencing online harms, both adults and children.

From witnessing violent content and online abuse, to fraud, we saw the Government develop legislative responses to these increasing incidents and frameworks that hold companies that run digital services to account.

In some ways, these harms were easy to identify as they mirror much of what we experience in the offline world.

I’ve been a long-time advocate of encouraging organisations to design ways to help people stay safe online and build the digital resilience of their users in the face of potentially experiencing a form of online harm.

By adopting safety-based designs into their user flows, including blurring violent content or prompting fraud warnings to improve reporting mechanisms when someone experiences harm, there are a multitude of ways to design safer products and services that go beyond preventative safety tech alone.

But what happens when some of these harms are less obvious to spot? And what happens when they are targeted at children and young people?

I’ve worked with Parent Zone over a number of years to think through and document online harms and ask the question, if we designed products and services to reduce online harm or support people when they experience it, what might this look like?

Recently, we turned our attention to child financial harms in games and other online apps. These are sometimes less well-recognised, or spoken about online harm.

In-game mechanisms can take the form of simulated gambling. One example of this is loot boxes, where young people pay for a chance to win a skin (a costume in a game) or some kind of tool to help them progress. These are slightly less easy to spot because they go under the radar.

Building on a wealth of research and analysis Parent Zone had been doing in this space, we wanted to take it a step further and start to think through what kind of things could help parents become more informed about child financial harms and help them make decisions about games and apps for their children to play in a variety of different scenarios.

We brought together parents with varying age ranges of children with an interest in keeping their children safe online when playing games and using other digital products.

We covered the following themes;

Age Rating

We asked parents what age ratings they recognised from a range of systems and their confidence in them.

Making choices on games

We asked parents what information they needed when making choices about granting access to games and putting in place safety mechanisms for their children.

Financial Harms and mechanisms within games

We asked participants to review a series of in-game mechanisms that may lead to harm for children and young people in both the short and long term. For example, ‘Simulated gambling’ or ‘In-app purchases’.

Making decisions on games and scenarios / Prototyping

Finally, we listed a range of scenarios, produced from Parent Zone research, which centred more on financial harms.

This was used to spark ideas and reflection from the group on what might help parents in making decisions.

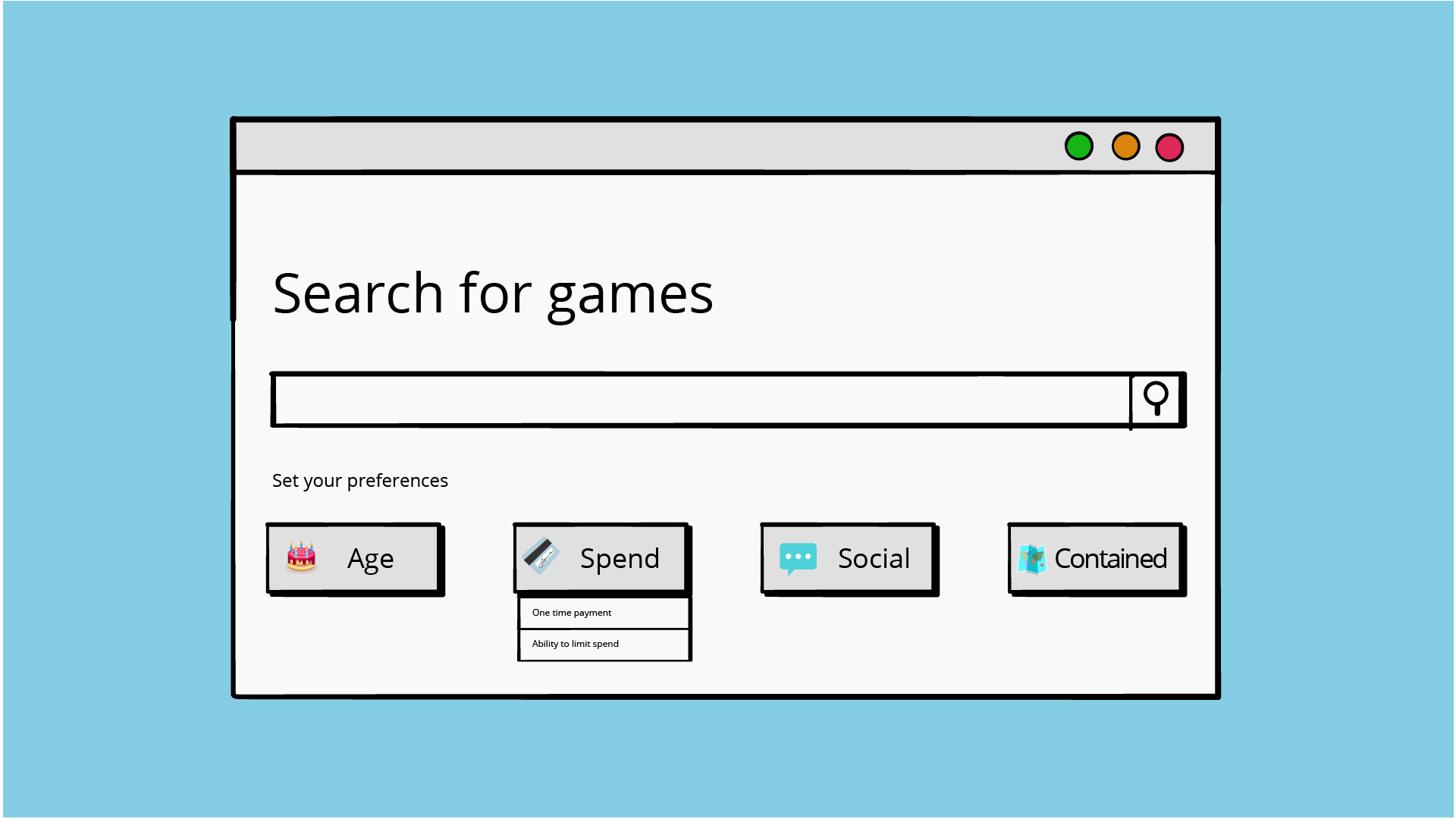

Using this discussion, we made prototype mock-ups of an imaginary digital product or service that would support parents in making decisions around games for their children particularly when considering financial harms.

A user-centred design approach

This was more than a traditional focus group, although the format may look familiar. We asked parents to actively prototype designs for a guidance tool that could help them make decisions about whether a game or app was suitable for their child.

This takes a design-led approach. Through this process, we are discovering the ways parents think about making decisions, where they feel confident and where they are less sure through an active collaborative design process. Because they are ‘physicating’ their needs into a ‘website design’, the features they list, the search terms and the things they’d like help with provide us insight on what they might need to identify and make decisions around child financial harms.

With this insight from the session, we turn it into a series of user needs and seek to validate these needs through repetitive research. These user needs allow us to come up with design hypotheses and early ideas that we think meet these needs. The needs focus on not defining a solution, more that many concepts can be developed in which to meet them.

"As a parent, I like to see the game for myself so I can decide if it is suitable for my child."

"As a parent, I need to understand what kind of in-game interaction there is, so I can decide if it is suitable for my child."

"As a parent, I would like to understand if a game has any kind of gambling mechanics, so I can decide if a game is right for my child or educate them to assure they are safe and can spot these mechanisms."

Our needs are written as if plural solutions could be applied. For example, understanding in-game interaction could be a series of logos sharing types of interaction, it could be an audio description of the game, or there could be many different solutions to meet this need.

Surprising Findings

We found that despite some parents saying at first, they had confidence in age ratings on games, we heard different strategies they use to check if a game is really safe for their children, from asking other ‘trustworthy’ parents to playing the game themselves.

So despite being confident at first, we uncovered more steps to ensuring games were safe. My reflection was that they had to do quite a bit of hard work to investigate beyond simple age ratings, that don’t provide much detail of what’s potentially harmful for children in a game.

Containment was another concern. Could parents be sure that if they purchased a game for their child, they would remain ‘in the game’ and not be given pop-up ads or be able to investigate and unlock other worlds and interact with people?

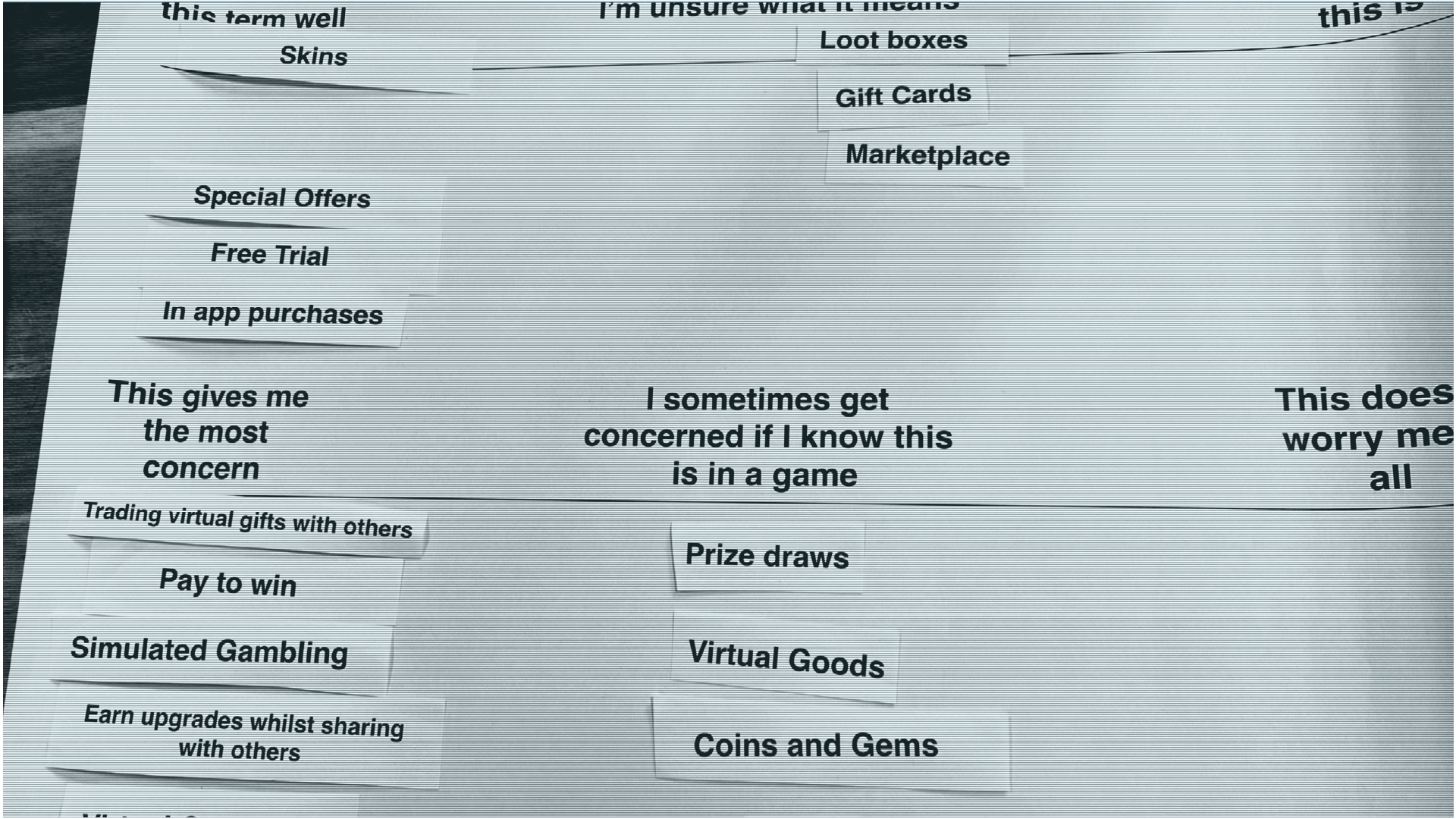

The words parents used were interesting, and don't match what we necessarily see in age ratings. Containment means no access to other worlds, or costumes when talking about ‘skins’ that children can buy in games. The term simulated gambling wasn’t commonly understood across the group, which is a standard warning in age rating guidance.

Child Financial Harms

Some of what we uncovered was validation for us rather than new insight which is a good thing.

In user-centred design, I often talk about having a hypothesis, a gut feeling about how something should or could be designed, and testing if this is true or not.

However, we were surprised that the room went from being fairly confident about making decisions using age rating information and their own approaches to making decisions on games to less confident when we introduced terminology around child financial harms.

We kept an exercise on financial harms until halfway through the workshop as our hypothesis was that quite a few of the terms would be unknown. We asked parents to card-sort terms they felt confident and less confident on from a list of in-game mechanisms that could lead to financial harm from simulated gambling to in-app purchases, loot boxes and skins.

“Chasing that buzz is a difficult feeling to get used to. You are teaching them to be a gambler”

I was surprised by the lower level of understanding when it came to more hidden methods of potential harm like simulated gambling or how in-game purchasing works.

The risk of their children developing gambling habits, unknowingly, was of great concern to parents. Picking apart loot boxes, lucky draws.

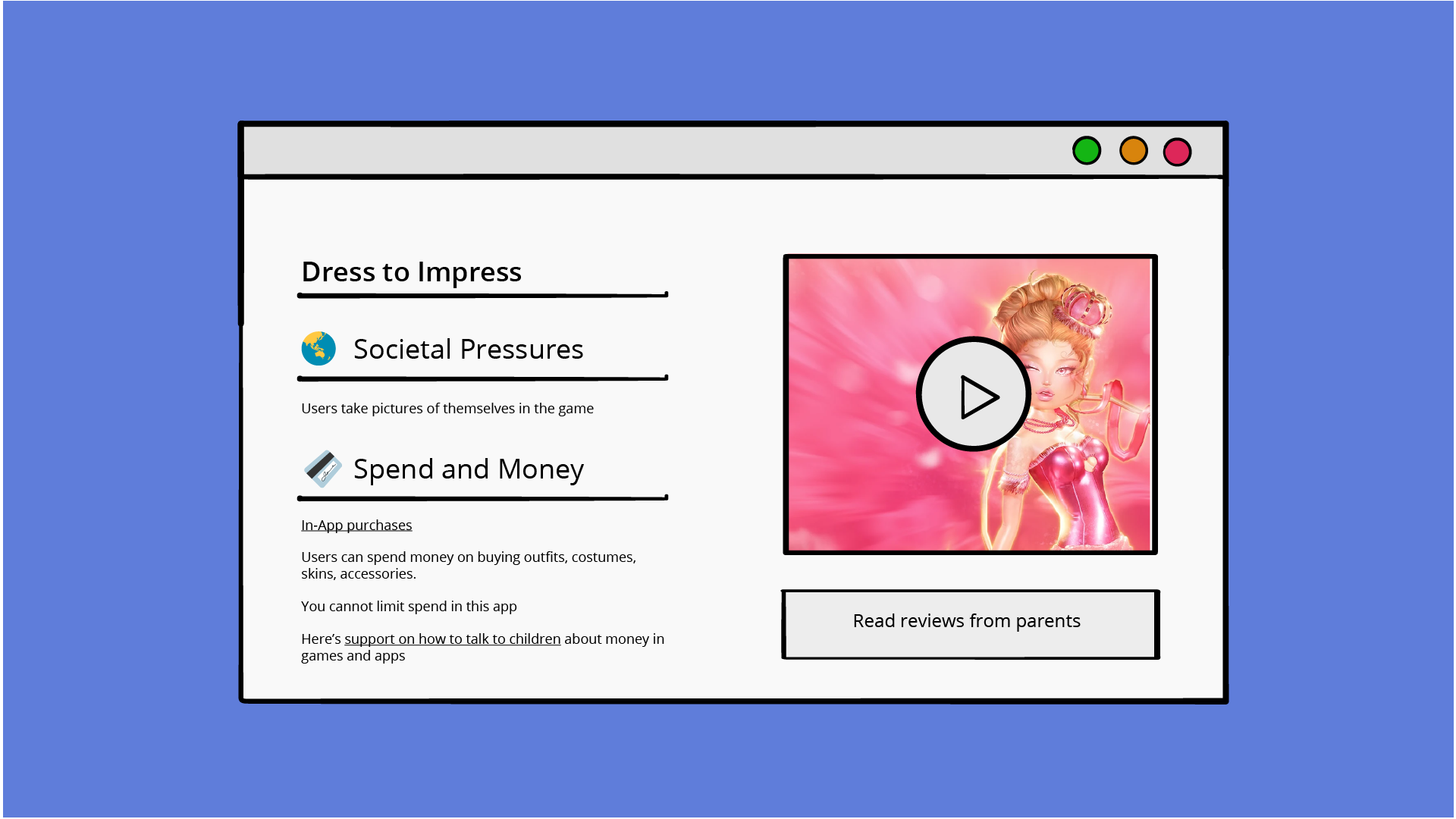

The other surprising insight was the realisation that skins, avatars and similar mechanisms were felt to mirror the in-person world of social pressure.

“I just wouldn’t want to have to play a game where I have to keep spending money to, like, make himself better, like, more superior than his friends at school. I just don’t want him to have that in the real world, which they will, trainers they have, holidays that they go on, things that they get up to at the weekend. It feels too much for a tiny 8-year-old”

These less obvious harms were things parents wanted to think more about after introducing the terms in their decision-making, and when we asked parents to design responses to help them make informed decisions about what games are right for their child, they focused more on the need to think through and be made aware of social pressures in games, gambling and potential overspend through in-game purchases.

User-centred design is about testing and learn

“Is a skin like a costume or avatar? If they said uniform or costume, I’d understand it”

Parents often preferred plain, everyday terms to describe some of the financial mechanisms. Language is important to help people identify financial mechanisms in a game.

If I were to redesign age rating information or a guidance tool that provides insight on the potential harms in a game I’d want to test the language I was using to communicate these and see if people understand what they mean.

As an early hypothesis, I’d break down in-game mechanisms and potential financial harms into the following as a starter for testing and ask parents to describe the words they’d use for these.

Prototyping solutions

I love using a design-led approach and co-designing potential solutions. We’re not asking the parents to design a product or service that can be used by millions of people. But by exploring what they need through sketching and prototyping we are able to ask more validating questions.

For example, one parent sketched a series of search terms to find information about potential online harms about games. This allows us to ask more questions about the terms they are using. Why that language, why those harms or in-game mechanisms?

This led to understanding terms like 'contained world’ that a parent used, in their mind meaning, there was no opportunity for children to go out of the game into other chat rooms, or interact with other players beyond what they had approved as a parent.

This approach is helpful because it gives us lots of insight into language, helpful functions, and what a product or service might be able to do without someone needing to say it out loud to you.

In-game spending was also a big focus, and after listening to parents talk about increasing bills and shock expenditure, many wanted more clarity on what kind of spending they needed to make for a game to be truly playable.

We came up with approaches post-workshop to start thinking about ways in which companies could be more transparent about their games, and/or parents could be better advised. These ideas came directly from some of the parents' prototypes.

Paid Content

How much of a game requires payment? Parents want a clear picture of how much of the game is behind a paywall or what type of content needs to be paid for.

Free

Free to download with no further spend or ability to spend. Is the game totally free, and if so, is there any other exchange taking place (like data tracking)? Parents want to understand if a game is truly free.

Free but requires in-game spending

Is the game free to download, but requires in-game spending? This means in order to play the full game or complete it, additional spending is needed.

One-off Payment / Pay Once

Pay for the game once, and it requires no more spending in-game.

Ongoing Payments

Does the game require a subscription to use, or are there regular costs over time?

In-game/app purchases

Clarify what kind of spending can be done in games and for what purpose?

This may need to be broken down into further strands. For example:

Marketplace purchases

Players can buy things that enhance their gameplay (e.g. Skins)

Simulated Gambling purchases

Players can pay for elements that simulate gambling (e.g. Loot boxes)

Limit spend

Ability to limit the spend based on a time-based metric, for example, spend up to £10 per month

The value of user-centred design

For me, user-centred design is really about testing and learning what works and what doesn’t, based on a good understanding of the needs people have and the context in which they use a product or service.

By testing some early hypotheses from this workshop we’re able to make the leap from research into actionable design. Of course, workshops alone won’t make a product or service, but the next steps I’d include is a range of designs being taken back out to parents to test whether they meet the intended outcomes built out from the user needs we established.

Those intended outcomes might include more confidence in parents making decisions on games for their children or a broader understanding of potential harms they can illustrate they’ve considered. Testing designs against these user outcomes allows us to know what works, and what doesn’t before we build it.

What can the industry do?

I would love to see an industry-wide investment into developing a range of features and design solutions that can be embedded into user flows in games that help both parents and children build awareness and understanding of the potential harms posed to them.

Similar to how we see repeating design patterns of ‘report this comment’ or ‘take a break reminders’ or ‘shield mode’ on platforms like Twitch, could we turn our attention to design patterns, repeatable solutions that help to alleviate varying forms of child financial harms.

A solution that can be applied to lots of games, marketplaces and bodies that support people in the event of harm being experienced. This could be applied at the decision-making point of downloading a game, inside gameplay, or when the event of an online harm takes place.

From clearer language on potential harms and pop-ups at the point of download to helpful prompts if a player is buying multiple loot boxes.

My first step would be to look at the user journey of making a decision on a game, to playing it, to a potential harm taking place and noting what kind of design interventions and/or features could be embedded into games. The easiest way to do this would be to get everyone who designs, makes and sells games in a room to identify potential solutions based on these journeys and the user needs Parent Zone and others have identified this space.

By coming together and co-designing these, we take the effort out of each company to try to find solutions themselves. Published as a pattern library, companies could take these designs and adapt them to their context.

This is a post by Sarah Drummond, Director of the School of Good Services.

If you’re interested in design patterns more widely about online harms, Sarah talked about design patterns and online harm on the Tech Shock Podcast.

The School of Good Services was founded by Lou Downe, author of Good Services and is co-directed with Sarah Drummond who led this research and analysis.

Sarah Drummond is the co-founder and ex-CEO of Snook, where she built one of the first and most successful Service Design practices in the UK from the ground up and went on to become the Chief Digital Officer of the UK arm of NEC Software Solutions UK.

Sarah brings a wealth of experience of building service design capability inside organisations across Government, third and private sector.